In the fold of the motherland

Growing up here with immigrant parents, I felt less American than my hotdog-and-baseball peers. It wasn’t until I went to Russia that I recognized how American I truly was.

This is a repost of an article I originally published on Medium in 2018, when I was having my Jupiter opposition, shortly after my Saturn return went exact. I’m currently gathering my thoughts on my recently completed Jupiter return, and wanted to have this here as a companion piece.

Growing up, people frequently referred to me as “Russian,” and it never once occurred to me to correct them.

I’m not actually Russian, even though my family is, and even though my first language was set in the vernacular of Pushkin, not Dr. Seuss. Most actual Russian children speak better than I do as an American adult, but I still remember the bewilderment I felt on my first day of preschool as a small child about to receive a crash course in English. I clung to my Raggedy Ann doll, and to the faceless adult who seemed to understand me.

I didn’t feel entirely American as a child, either — at least not in any unadulterated sense of belonging. I loved eating Bomb Pops on the Fourth of July because they matched the red, white and blue of my outfit (but mainly because they gave me a sugar high). I also envied a lot of my friends, whose kitchens were stocked with processed snacks deemed desirable and cool by youthful consensus.

My family’s table was equal parts hamburgers and pelmeni — a mix of the accessible and the extralocal. Sour, pickled vegetables and inscrutable beet salads were not appealing to my young taste buds, and they often sat untouched, deemed too weird to digest.

I was (and continue to be) a weird individual, but it was hard to tell where the “me” of it ended and the “immigrant” began. That first alien experience of people my own age was a formative one. As a girl of 12 in suburban New Jersey, I shrunk in grocery stores behind my mother and grandmother, praying that no one I knew would hear us speaking in Russian. I’m only couching all of this as one giant food metaphor because it’s the most immediate example that comes to mind. The whole of it, this “othering,” is hard to describe unless you’re familiar with the feeling of “not exactly.” Not exactly the right food, or the right clothes, or the right words, or the right mentality. Sports culture, for one, has always eluded me. It wasn’t until I was much older — high school, maybe — that I realized bilingualism could be seen as cool or interesting.

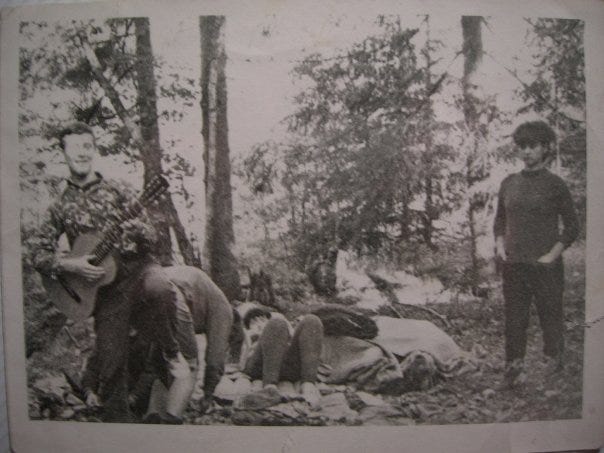

Eventually, I leaned into my roots with a sense of pride. I was taken in by the evocative poets and nostalgic songs all written in a minor key. I laughed at all the predictable jokes involving communism and spies. I appreciated the bittersweet history and how my own ancestors lived through it. All four of my grandparents were certifiable badasses who survived exile in Siberia and/or fought the Nazis, and my parents left behind a Russia where people stood in line for toilet paper and whispered their dissent.

The whole of it, this “othering,” is hard to describe unless you’re familiar with the feeling of “not exactly.”

I even appreciated the disillusionment to some extent. The world-weary affect of the Russian seemed so out of place within the unrelenting optimism of America, but maybe that’s why I felt a complicated affection for it anyway, even if my parents’ cynicism drives me crazy sometimes. Like so many immigrants from so many countries, my mom and dad left a troubled home to come to the United States in search of something better — the hopeful exclamation mark of America — but they were too accustomed to the lies and institutional failures of the Soviet Union to ever lead with the benefit of their doubt again.

After nearly 30 years of talking and thinking and hearing about the country of my ancestors through these filters, I finally visited Russia for the first time last month. My family had been planning this trip for years, but the timing never felt entirely right, and political tensions were often a large part of that.

That we went now, of all times, is an irony that wasn’t lost on me. Days after the U.S.-led strikes on Syria labeled an “act of aggression” by Putin—which took place just a month before our flight—we had a frank conversation about whether we’d have to cancel our trip. But by then, it had largely become a matter of “if not now, then when?” Maybe I’d live to see a true sense of solidarity develop between the U.S. and Russia — when provocations like these no longer fell somewhere within the range of “business as usual” — but my parents weren’t confident they would.

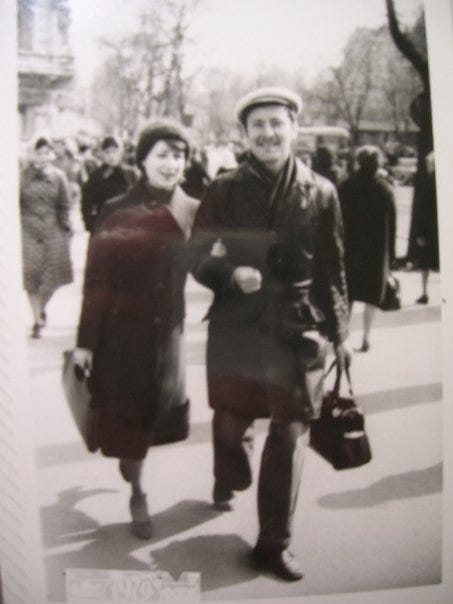

My mother had waited long enough: 38 years, to be exact. My dad had gone back to visit a couple of times since they’d left, but she was my age the last time she set eyes on Russia. If this were a science-fiction movie set in the era of Soviet space exploration, my mom may as well have pushed a button and woken up the next day, still age 29, but as the next incarnation of herself (me) in the next incarnation of her country (the Russian Federation).

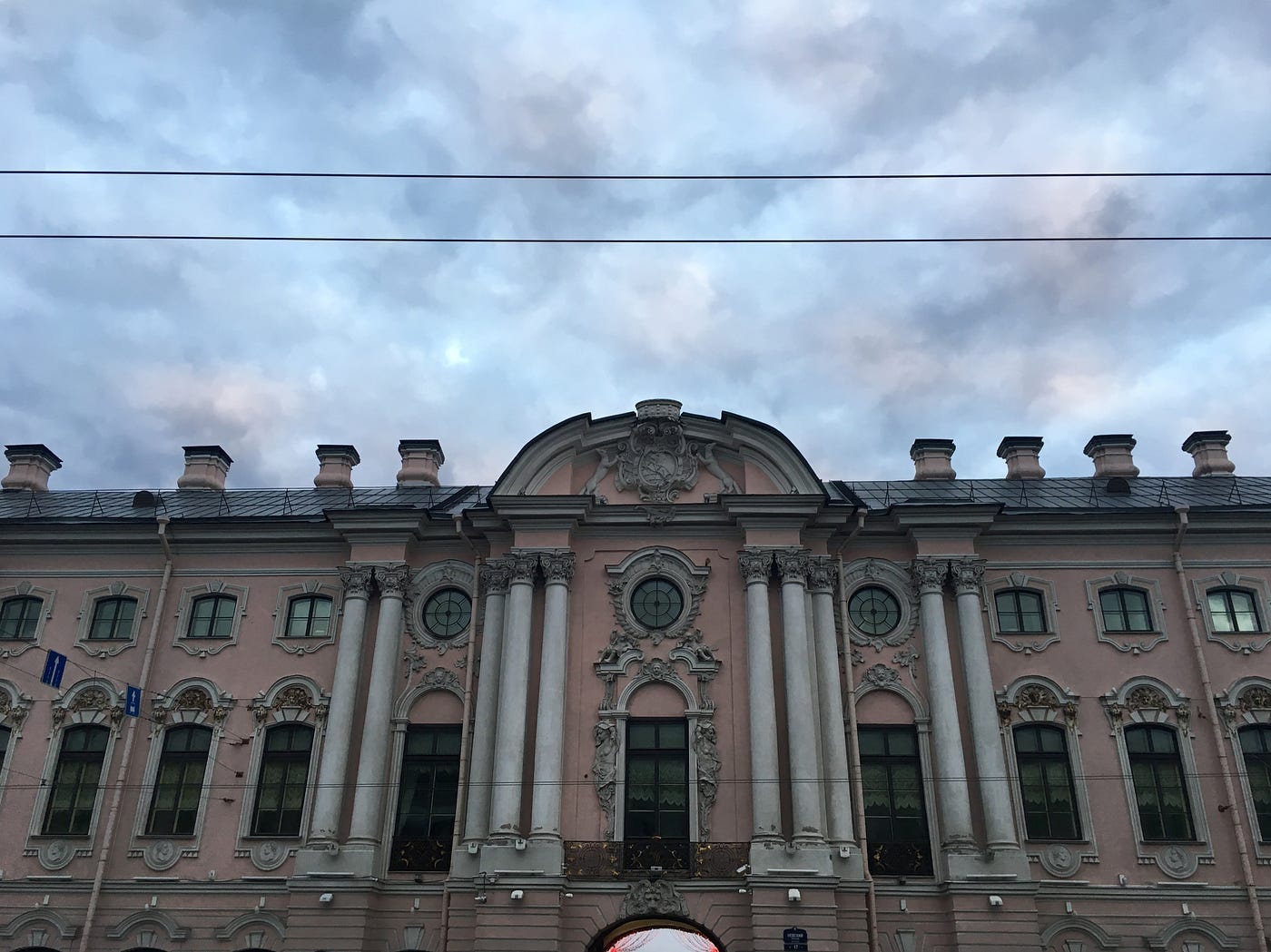

Things were not as she’d left them. The sober, Stalin-era buildings had been lightened up with soft, yellow coats of paint. There were restaurants and coffee shops on every block, and there was no shortage of places to spend your money. Moscow and St. Petersburg are now largely an extension of Western Europe — if not in soul, then at least in appearance.

My dad’s cousin, who joined us in Moscow, pointed to the McDonald’s on Pushkin Square and recalled her memories of its grand opening in 1990. People formed lines all the way up and down the block to get a taste of a Western export made for efficient consumption that they could barely afford at the time. And like a canary in a coal mine for crumbling regimes, it accurately predicted the official downfall of the Soviet Union the very next year.

At the moment of this fast-food debut — of America landing on the moon and planting a flag marked with two golden arches — the New York Times printed the words of Stanislav Kondrashev, an analyst for Soviet state news publication Izvestia, who called it “the expression of America’s rationalism and pragmatism toward food.”

“The contrast with our own unrealized pretensions is both sad and challenging,’’ he wrote on the front page, recalling old Kremlin vows to commercially bury the West’s cola industry with Russian kvass and its pasta craze with stuffed Siberian pelmeni. “All that has turned to sand,” he rued.

To be fair, things weren’t as my dad remembered either, though he’d been back as recently as 2014. We drove to Zagoryanka, a small town on the outskirts of Moscow, to visit his father’s grave and the house where he grew up. There were only fences — the tall, impenetrable kind designed to shield everything from view. A small dog barked passionately in the yard, and the house had been torn down and replaced with a facade my dad couldn’t recognize. Down the street, the bus stop looked like it hadn’t been touched since the ’50s. Compared to the immaculate cityscapes of downtown Moscow and its well-maintained (and well-policed) lawns, this was a display of worsening, and of disrepair. It bummed my dad out for the rest of the day.

As for me? I’m not sure what I was personally expecting to discover in Russia, aside from a first-hand reference point for all the stories I’ve been told about this place — both from my family and from the remnants of America’s Cold War anxieties. For the most part, the Russia I saw was one of restaurants, museums and selective economic triumph belonging to the few — and most readily on display for visitors like me.

We came as tourists, not time travelers. And yet I still hoped I’d feel a sense of recognition. Of knowing. And it did happen for me once or twice.

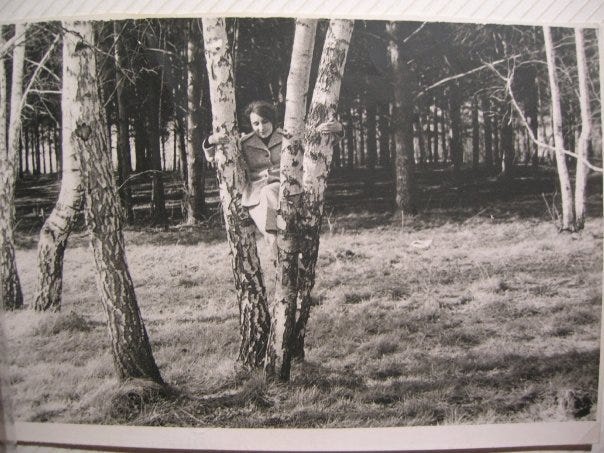

The most connected I felt to this country was in the places where man had not entirely intervened: in the woods of the Kolomenskoye estate; in the blurred shapes of trees that swooped by me on the train to St. Petersburg; in the intermittent splashes of nature that framed the city blocks. Here was something that felt immediately familiar and accessible: birch trees and red squirrels with tufted ears, just as they had appeared in the illustrations of the children’s books that put me to sleep every night as a child.

I’ve never seen so many lilacs in my life as I saw in the Moscow and St. Petersburg of mid-to-late May. I used to have a lilac bush growing beneath my childhood bedroom window, and every May for the last seven or eight years, I’ve made it a point to encounter at least one in the wilds of Boston or New York so I can break off a little branch and bring it home with me. In Russia, they line the streets. This perfumed scent trail has been tethering me to my childhood all along, and I guess, now, something even older than that.

My encounter with Russia became an encounter with paradox. On some level, I got what I came there for: a sense of connection with the literal land of my ancestry — the dirt and trees and flowers and birds. But the cultural mirror provided to me there made me recognize just how American I actually was: reflexively smiling, invested in my convictions, expecting, deep down, a happy ending…informed by an immigrant legacy. That I ever felt a sense of alienation in the United States is perhaps the biggest paradox of all.

I kept thinking, instead, about an article I read once that used a pretty upsetting visual to illustrate how little time we all have left with our parents. By the time we graduate high school, we’ve already spent 93 percent of the face-to-face time we’ll have with our parents over the course of our entire lifespan.

The intersection of our lives, it turns out, isn’t terribly substantial. But I was privately moved during one of our walks, which was like every other walk except for my acute awareness that we were making up for lost time, retracing steps my parents once took long ago in Moscow before I became a timeline that could overlap with theirs.

How nice it is that we could elaborate on that spatial memory, adding some sort of conclusion to the abrupt question of their departure and all that once lay ahead. And how nice it is to walk side by side like this together, if only for a moment, if only for a while.